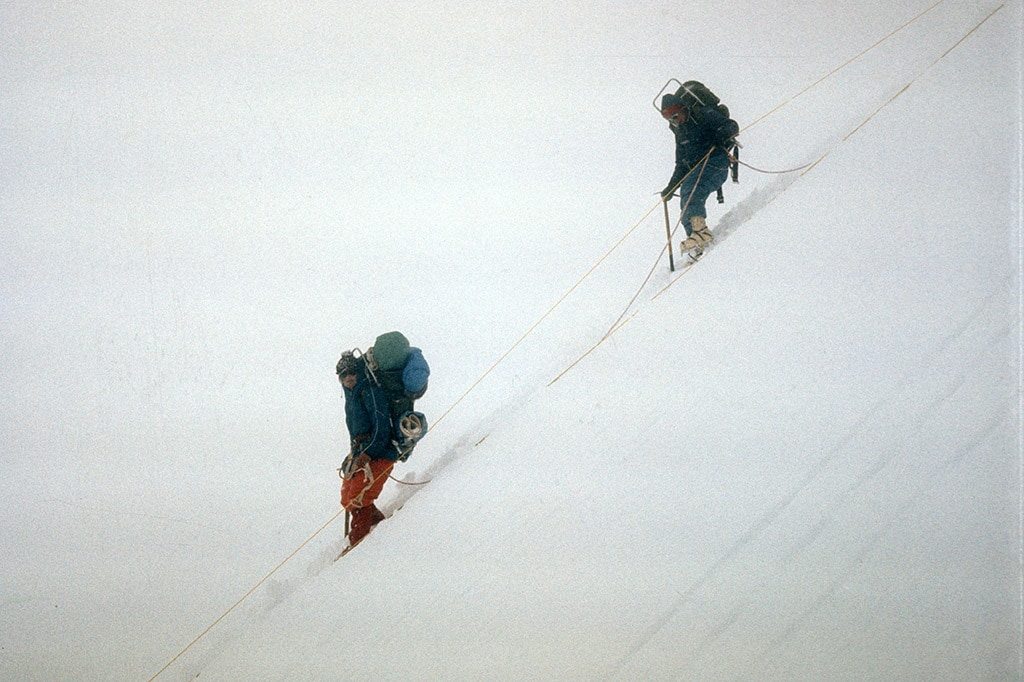

More than half a century ago, amid snow-covered rock ramparts rising on either side like some giant’s hallway through a wintry lair, six women set out to do what the rest of the world thought was impossible. It was 1970 on the slopes of Alaska’s Denali, one of the world’s biggest mountains, and these six were making for its wind-hammered summit in the first all-female ascent of North America’s tallest peak.

This was the scene I was transported to a few years ago. I’d just opened an email from my literary agent that contained a single line, “Is there a good story here?” and clicked on the link she’d sent to a short National Park Service blog post. The post commemorated the 50th anniversary of the successful—albeit incredibly harrowing—expedition organized by six women calling themselves the Denali Damsels. This was no small thing. By 1970, we had sent men to the moon, but women had yet to stand on the highest points on Earth. Popular belief, propped up by reporters, magazine editors, and much of the climbing world, still held that women were incapable of withstanding high altitudes, savage elements and carrying heavy loads up storm-ravaged slopes without men’s help.

I’d been writing about adventure and women’s issues in the outdoors for several years by then, and as a recreational adventurer and REI Co-op Member, I’m well steeped in the mountain world. Yet, I’d never heard of this boundary-breaking climb. Why wasn’t this achievement more widely recognized, like Lynn Hill’s famous free climb of the Nose in Yosemite or Alex Honnold’s free solo of El Capitan?

As I researched, I realized this climb wasn’t only the first all-women’s summit of Denali. It was the first all-women’s ascent of any of the world’s high peaks. Not only that, it was also an improbable tale of survival.

So, yes, there was absolutely a good story here. But why had it escaped widespread notice and celebration before now, and largely faded from the historical record?

When we think of the stories in mainstream adventure and exploration literature—and, thus, which stories become immortalized—the first that come to mind are likely ones like Into Thin Air, about a fatal storm on Mount Everest, Touching the Void, about death and survival in the Andes, or The Emerald Mile, about the fastest boat run through the Grand Canyon. Stories that feature women, though? Although more adventure books about women (and by women) have come out in the last few years, when I began working on my book Thirty Below, about this Denali ascent that published in March of 2025, I couldn’t think of any off the top of my head that had been culturally enshrined as widely known stories, other than a few memoirs, like Cheryl Strayed’s Wild. As a writer and as an adventurer, there were breathtakingly few examples to look to.

While there are plenty of strong and complex women in the canon, there’s still a noticeable gap in the stories that tell of female mettle, bravery, curiosity and impact—on how we see the world, what we know of the world, and what we are capable of in it. Gender lens aside, the fact that they’re not as well-known means we’re missing out on good adventure stories, period. These stories do exist. And it’s time they received their due.

Grace Hoeman developed the audacious idea to organize and lead an all-women’s ascent up Denali, a massive mountain infamous for its fierce conditions. Everyone told her and her six-woman team it couldn’t be done—and sometimes hurled insults for emphasis, according to archival and other research I did while writing Thirty Below. An Alaskan doctor and mountaineer, Hoeman had been told she had “illusions of grandeur” and “light experience,” even though she’d climbed on several continents and had multiple first ascents to her name across Alaska’s rugged peaks, including in the Talkeetna Mountains, the Brooks Range, and the Alaska Range. She also soloed five first ascents, including Mount Wickersham and Mount Palmer in the Chugach Mountains. Arlene Blum, a California climber and the team’s deputy leader, was told that there was “no way dames could ever make it up that bitch,” “women climbers either aren’t good climbers or they aren’t real women,” and “women should be able to climb Denali more readily than men—after all, they have all that extra insulation.”

I found these comments while poring through letters, books, archives, articles, journals, and conducting first-person interviews on the wild stories that had shaped the narrative of women’s climbing. We’ve come so much further today—all-women’s expeditions are common, and although we haven’t achieved parity, professional female mountaineers, climbers, and guides are no longer a rarity—that it’s easy to forget how different the reality was for a long time.

Some stories were just ironically funny. At the turn of the 20th century, when women were ridiculously expected to climb in skirts that left them struggling with heavy and often wet fabric, Irish alpinist Elizabeth Le Blond would shuck her skirt and hike in her knickers instead once out of sight of villages or huts, and then retrieve it after the climb. Once, an avalanche carried her skirt away from its hiding place. Back in town, she had to hide behind a tree while her guide fetched another from her hotel room. He returned carrying … an evening gown.

Most stories are far less humorous. In 1959, female French alpinist Claude Kogan led a 12-woman team —supported by male guides and porters—on what was to be the first all-female ascent of Cho Oyu, the world’s sixth highest peak. Kogan, one of her expedition mates and two Sherpas were killed by an avalanche at their high camp at 23,000 feet before they could attempt the summit. In a dispatch after the tragedy, British reporter Stephen Harper called it “a verdict that even the toughest and most courageous of women are still the ‘weaker sex’ in the white hell of a blizzard and avalanche-torn mountain,” claiming that “in the face of violent death and peril, men go out in front and women accept it.”

In 1961—just nine years before Hoeman and Blum organized their Denali climb—Sir Edmund Hilary barred American climber Irene Miller from setting foot on the fifth-highest peak, Makalu, as part of his expedition; she would go no farther than basecamp. According to Blum’s 1980 climbing memoir Annapurna: A Woman’s Place, Miller was told that if she wanted to join the expedition, she’d better be willing to sleep with the men on the team—even though Miller had gone to Makalu basecamp with her husband, who was one of the climbers.

If anyone had the mettle to deal with this kind of absurdity, it was Hoeman. Born in the Netherlands, she began studying medicine at 21— in Berlin in 1942, two years into Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. She wanted to be a surgeon at a time when fewer than 4% of doctors were women; Hoeman was willing to brave Nazi Germany to study in Berlin at the best university. Within a year, she fell in love with a fellow doctor, married him and became pregnant. Her husband, drafted as a battlefield medic, was shot and killed in combat two years into their marriage—while Hoeman was pregnant with their second child.

After she finished her degree, while single-parenting a two-year-old and giving birth to her second daughter in the midst of war, her mother (perhaps an inspiration for Hoeman’s mettle) hopped on a bike in Holland—she couldn’t afford a car—cycled to Berlin, found a bike for Grace, and together they rode the little family out of the rubble of wartime Germany back home to the Netherlands.

Twenty years later, after leaving Europe for advanced medical degrees at Yale and Syracuse Universities in the U.S., Hoeman would end up in Alaska and fall in love again—this time with those massive, wild mountains.

Hoeman’s story drew me into writing Thirty Below. She epitomizes a complicated, real person driven by her own internal stakes. As I began getting to know her through archived letters and journals, I loved her. By the end of researching the Denali climb, I could have joined the other women on her team in wanting to strangle her for making decisions that very nearly killed them all.

Hoeman was complex and three-dimensional—as were the rest of the women on this climbing team. None of them were clear-cut saints or sinners. Some made choices that were (shocker) selfish. They each had their own stakes, own emotional weight, own pressures they were under as they faced the frigid sub-zero temperatures, savage wind, and fierce whiteout storms for which Denali is famous, on top of deadly altitude sickness and the criticism of a men’s team climbing at the same time. And all of them were aware of the one pressure they were collectively under. When disaster struck at the worst time on their expedition, the team’s actions would decide not only their fate and how the world would judge them, but also all women’s ability to climb and survive the fiercest mountains.

I’m a nonfiction writer, but I prefer reading fiction. Here was an opportunity to write a true story with all the elements of fiction that I love: character development, nonstop action and a surprising ending. To help fill the void in our canon, I wanted to write a book people couldn’t put down. Which was, frankly, easy; there was nothing boring about what happened on Denali in the summer of 1970.

I still can’t fully answer the question of why this story, and so many other women’s stories, went untold for so long. I believe that part of it is how uncommon these particular women were for their era. Even still at the time of the Denali ascent, folk wisdom about women undertaking arduous physical activities ran rampant: their legs would become large and unsightly, they might grow mustaches, they might not be able to bear children; in fact, their uteruses might fall right out of their bodies. A limited women’s college sport championship schedule wasn’t announced until 1969, and Title IX, which recognized gender equity in education, including school athletics, wasn’t passed until 1972.

Just one month after the Denali expedition, in August 1970, 50,000 women strode down New York City’s Fifth Avenue with linked arms in the Women’s Strike for Equality March, putting second-wave feminism on the national map. Had the Denali ascent unfolded even a year after it did, in the fevered days of a new feminist movement, perhaps it would have received the honor it was due at the time. But also in 1970, the narrative persisted in many pockets of the climbing world that any route or summit achieved by a woman was deemed too easy for men to attempt again. And this, after all, was Denali: one of the most sought-after prizes in mountaineering.

It’s also sadly true that stories of failure tend to resonate more loudly than those of success. After all, failures often serve as proof of whatever narrative it serves the dominant population to reinforce, however erroneous that narrative is. Consider this: although Hoeman’s team climbed Denali and managed an improbable self-rescue at a time when people who collapsed at the top of the mountain often died there, no national newspapers covered the feat. But two years later, Blum read with astonishment about another team attempting “the first” all-women’s summit of Denali. Three of the women disappeared on the descent, and their bodies were found at 15,000 feet. The Los Angeles Times and The New York Times covered their deaths in three short paragraphs. Neither article made mention of the two survivors, nor celebrated the fact the whole team had made it to the summit.

Some success stories, though, do get told. Like the fact that five years after the Denali climb, in 1975, Japanese climber Junko Tabei became the first woman to summit Everest. Three years after that, Blum herself led the expedition that put the first women, and first Americans, on top of Annapurna I in the Himalaya, said to be one of the most dangerous and difficult of the world’s high mountains. Both are much more widely known feats than the 1970 climb, even though it was the first all-women’s summit of any of the world’s big peaks.

“Historic firsts are important as they set the bar for what is possible,” that National Park Service blog post read. “The stories of these firsts sometimes become common knowledge in certain communities, or grow into legend, while some feats fade as time passes.”

The six women who took on Denali, and the world’s perception of female climbers, are some of those women that history unjustly forgot, though they deserved a lasting place in the annals of adventure. There are, no doubt, many more stories like theirs, perhaps waiting for the one that opens the floodgates to all the rest.

Thirty Below: The Harrowing and Heroic Story of the First All-Women’s Ascent of Denali, is available for purchase in REI stores and at REI.com.