Nature’s great diversity includes a wide range of what might be considered LGBTQ+ expressions. From frogs and fish that change gender to intersex plants to a famous male penguin couple in New York City’s Central Park Zoo, same-sex behavior has been observed in more than 1,500 species globally.

For REI Co-op Member, naturalist, educator and creator Jason “Journeyman” Wise, identifying—and teaching others about—the queerness reflected in the natural world has been a great catalyst toward not just self-acceptance and love, but also a way of decolonizing our ecological perspectives. To him, “queer ecology” means exploring the myriad ways nature defies the rigid, Westernized interpretations that many of us have been taught in traditional settings and textbooks. Now, Wise leads full moon hikes, foraging expeditions, and queer ecology walking and hiking tours in and around Los Angeles, but his path to the outdoors wasn’t always a straightforward one.

Here, he shares how he found himself out on the trail—in more ways than one.

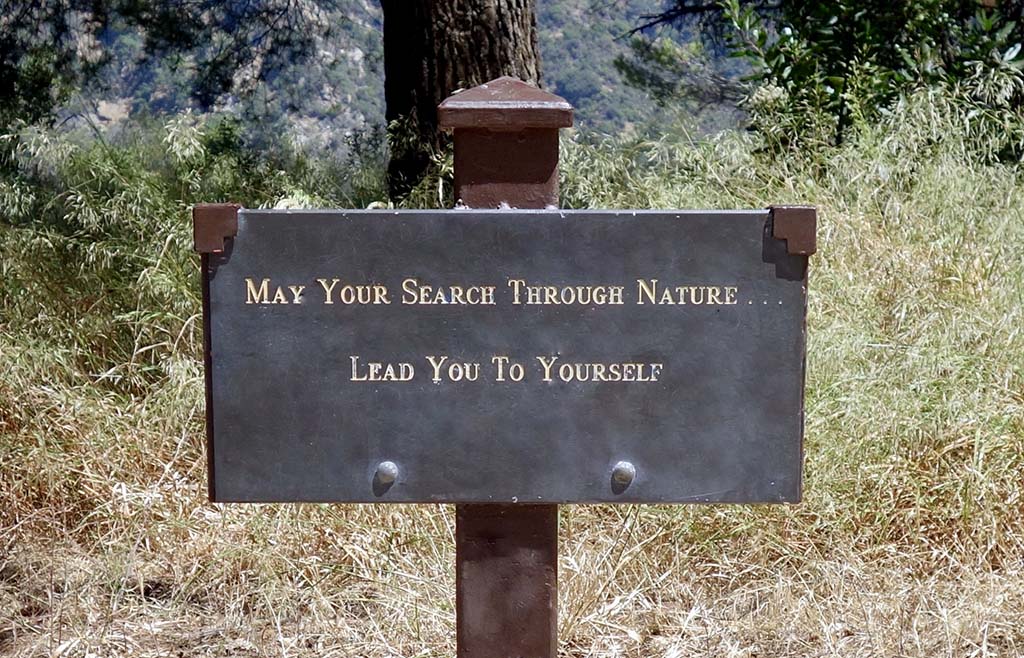

I always thought I’d be considered a freak just for being me, so I told myself to pursue the expected life. It was a torch that guided me like a headlamp on a night hike, from childhood in a small town to adulthood in the big city—searching for community, safety, identity—until finally one day I turned the lamp toward myself and realized I had always been heading toward an unexpected life instead, and nature was my throughline.

Memory is a funny thing. Most of us don’t actually remember childhood details; as adults, we piece random bits together to form a narrative. These are the stories we tell ourselves, how we define ourselves—from celebrating the joys we hold dear to the traumas we want to forget but never will.

In my narrative, I played outside as often as possible. Growing up in a small town on California’s temperate central coast afforded ample opportunities for this. I gardened with my mother, camped with my dad and brothers in Yosemite, imagined entirely new worlds on my own and, when I was inside, watched every nature documentary to marinate in the knowledge, ready to blow my brothers’ minds with the fun facts I’d acquired.

Then, at 11 years old, I learned why I felt like the odd one out all the time—though at the time, it wasn’t a realization I’d hoped for. I finally understood that I’m gay.

Nowadays, this isn’t always a shocking declaration, but I was a young kid in the ‘90s, brought up in a small town and a conservative church. Everything I knew up to that point about being gay was that it was not OK—it was downright dangerous. I had no gay role models to look up to, but did hear about gay bashings and the AIDS death sentence. I didn’t want to be “out,” I wanted to be “in.”

So, I channeled my internal conflict and fear toward the biggest project I’d ever undertaken: I would become straight. And part of that meant giving up my time and connection to nature.

First, I tried church as my “in,” but it didn’t work. I couldn’t pray the gay away.

Next, I used every imaginable teenage rebellious phase as a potential “in”—raver kid, straight-edge punk, party guy. I wasn’t rebelling against my parents, though; I was rebelling against myself.

I moved to Los Angeles, getting further away from the nature that infused my childhood and joined a fraternity; another attempt at staying “in.” Maybe here with the social and dating opportunities, I could finally be straight. But it didn’t work—even worse, I felt like I was leading everyone on. In the end, that’s what pushed me out: my empathy. I had to live my truth so I could stop lying to everyone around me.

I came out to the women I had dated, and became friends instead.

I came out to myself, and became friends with him too.

My out era had begun, but soon I realized that it didn’t look all that different from those who are “in.” Dates, happy hours, friends, a political science undergrad degree, commuter traffic, breakups, an office job, a partner, an environmental policy master’s degree, more happy hours, more traffic, a “dream” job, a windowless office. It was typical—and in typical fashion, it all became a grind.

Not that it was all a grind. In fact, I was passionate about that nonprofit job, especially as it allowed me to do something I’d enjoyed as a kid: sharing those fun facts. In this case, though, it was fun facts about how to advocate for a better world.

Life in the progressive big city allowed me to be myself, but somehow I still didn’t feel completely free. I thought there was something missing that I couldn’t quite pinpoint. Something I was about to realize was with me all along.

Finding a Way Outdoors

Now in my early-30’s I knew I needed to shake up my life, so I decided to take on a physical challenge: I’d complete a half marathon trail run while fundraising for a good cause. My dad ran marathons when I was a kid, so it was a way to follow in his footsteps. My body and mind needed a new purpose, and it was a way to foster endurance and resilience. It also didn’t hurt that the run happened to be in Hawaii.

I trained for months in the Los Angeles mountains—opening my eyes to the nature that surrounds the city like a geographic bear hug. Through too many twisted ankles and charley horses to mention, I completed the half marathon in Oahu’s rugged Windward Shore. Summoning my father’s fortitude, I admired the incredible landscape, unlocked memories of my nature-minded childhood and imagined ways to re-engage with the outdoors and share its beauty with others.

The half marathon was over, but when it came to challenging my expectations, I was hungrier than ever. I wanted to keep running outside, but also wanted to slow down. I wanted to listen to the birdsong, not the jock jams on my headphones. I realized that just being in nature was helping me process the grind and find peace from city life. I needed more of it.

When I wasn’t running, I started spending time outside in other ways. At home, I channeled my mother’s gardening spirit, relearning the joy of soil-covered hands—from a lowly discount-store potted plant to growing garden vegetables. If I was happy, I’d go on a hike. If I was stressed, I’d pull weeds in the garden. If I was angry, maybe a little of both.

One morning, after a mild to-do-list-related panic attack, I called in sick. I needed a mental health day to escape the windowless office and be in peace outdoors.

Every single hike leading up to that day had taken me toward the trailhead that day, to what became the start of a new path. That particular day, I decided I didn’t want to keep following it in fits and starts—I needed to go all in and start a new journey of life.

In 2015, with my partner’s help, I quit my job.

Inspired by Cheryl Strayed’s seminal memoir Wild, I set off on a solo trip across the breathtakingly remote landscapes of the west—although by Prius, not by foot.

This was a path toward an unknown future, but at least I knew the view would be better than a windowless office.

The journey was indeed wild. It had been decades since I’d slept in a cramped tent or started a fire. It had also been decades of busyness and phone distraction since I’d been alone with my thoughts. I struggled on all fronts. At a fork in the road in Moab, Utah, days into this new journey, I sat with a decision: I could turn left and be comfortably home in LA by sunset. Or I could turn right toward Yellowstone and truly get lost, hopefully to find where I was always meant to be.

I saw cars approaching in my rearview mirror—it was decision time. I had come all this way, in miles and in life, and there was no way I could turn back now.

I turned right—I let myself get lost, in the hopes that I would eventually find myself. First, though, I finally figured out both how to sleep through the night in that cramped tent and to keep a fire burning. I was proud of that. I also got to know myself—not as someone to battle against, but as my best friend. I was proud of that even more.

For the next few weeks I camped, hiked and reignited my own fire across the Rocky Mountain magic of Yellowstone and Glacier, into the flourishing cascades of Mount Rainier and Mount Hood, and through the spellbinding Redwood fairy rings and intimidating coasts of my home state. But before I got home to LA, I went home to Yosemite. Back where I’d camped as a kid with my dad. Back to the self I thought I had to give up when I came out.

On the drive back to Los Angeles, I reflected on what I learned or didn’t. I realized I had even fewer answers to my questions about the future, but I did figure out my past—how each step led to the next and how vital they were for who I was now. I figured I’d just keep on hiking down this path to see what came next.

Finding Queer Nature Everywhere

With a completed journey in my pocket, I began to reengage with the outdoors in my big, bad city. I meticulously began tackling the hundreds of local trails and campgrounds framing this metropolis, and instead of running or driving past, I slowed to soak in all the biospheric details.

While I’d rather have frolicked in the forest, I also needed to pay my bills, so I volunteered to help find a purpose and possibly a career. Venturing deep into the San Gabriel Mountains, I met up with some grungy and kind folks from TreePeople for a habitat restoration project, planting native plants. I’d heard of those and seen many on the trails, but I didn’t know much else about them. After a short introduction and training, I was handed a pot with a delicate, fragrant, pale green plant.

Its vivid scent cascaded directly into my memories, transporting me from the San Gabriel Mountains back to the campgrounds of my youth. I hadn’t known what that scent was as a child, yet somehow I still knew it now, deep down in my soul.

This plant, like nature as a whole, was always my throughline. It was with me through it all, keeping me grounded, connected, calm.

That day I learned about California sagebrush, called “cowboy cologne” for its sweetly unforgettable scent. I learned about coast live oak, California lilac, showy milkweed. I learned that Mother Nature reflected all the diversity I loved and cherished in the LGBTQ+ community. I learned that she holds no judgment for anyone or any thing. I learned that this was all I ever wanted to learn again.

So I went back to school. I had that environmental policy master’s degree, but I’d never learned about the hawk moth and sacred datura’s symbiotic relationship. Or about the gay penguins at the Central Park Zoo. Or that nature is always so close, whether it’s on a mountain peak or sprouting through a crack in the concrete.

I continued to volunteer—growing trees from seeds, planting trees and teaching others to do so—before one seminal job, returning to Yosemite to teach about the biggest trees at the Tuolumne Grove with the Yosemite Conservancy. Finally, it all clicked into place; I was where I always needed to be. As much as I loved learning about nature, it was teaching about it—sharing those fun nature facts with my brothers, then my friends—that truly gave me joy, because I got to share that love with the world.

I soon discovered opportunities to teach kids on their school playground or on field trips at the LA River. I realized that I loved teaching in the city even more, because blowing their minds with the nature in their own neighborhood was even more rewarding than showing them epic views of Yosemite.

I also began to tie together so many loose ends of my identity. I led my first public “queer ecology” walks, creating the space I needed as a young gay man in the city—a space to connect, to love and to cry. I gave myself the ability to express how much I had learned: what I thought I had to give up to come out, until I realized that we never have to give it up because Mother Nature will always be with us. But mostly, empowering my LGBTQIA+ community through nature and sharing my story as a form of group therapy, an expression of my and all of our truest selves.

This journey has never followed a straight path, so why would it start now? As it did for so many of us, the COVID-19 pandemic threw numerous roadblocks on the path. Without the ability to teach in person—and I really wanted to teach—I started making video lessons for social media instead. This is when I realized how important access to education about the natural world is essential to cultivating strong environmental advocates.

One of those environmental education videos became a viral video. With that following, I was able to get paid to make some of those videos, and was profiled in The Los Angeles Times. As COVID restrictions were lifted I began leading hikes for all ages on trails across Southern California: I now host regular outdoor educational educational events and tours like foraging outings, full moon hikes and explorations along the LA River. Now, as an outdoor and online environmental educator, I can blow millions of minds over the wonders of Mother Nature.

I once thought I had to give her up in order to be free, but she reminded me I was always free—I just had to slow down and breathe to find out.